In 2006, there was a major breakthrough in stem cell research - Japanese researchers discovered that it is possible to “reprogramme” specialised adult cells into cells that behave like embryonic stem cells, which were termed induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). iPSCs share common features with embryonic stem cells (ESCs), such as being pluripotent and having the capacity to differentiate to specialized cells such as nerve or heart cells. The technology is very new and researchers are still trying to understand what happens to the cells during the reprogramming process. Our aim with this project was to understand how the epigenome changed, when cells were changing their cell identity. More specifically we wanted to know what was happening to the DNA methylation marks during the reprogramming process.

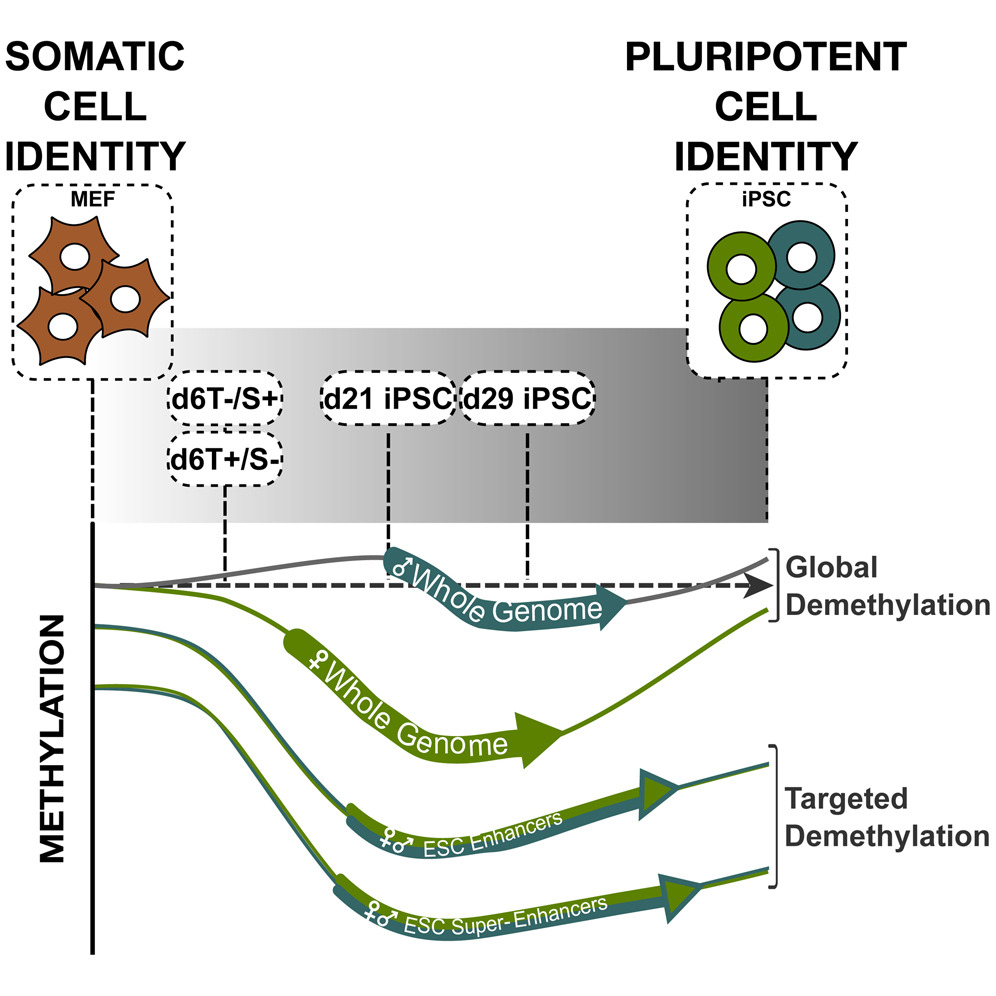

We found that cells undergoing reprogramming change their DNA methylation marks both globally, which is important for cells to “forget” they were differentiated, but also on a more local level, so cells can acquire a pluripotent cell identity (similar to ESCs)*. It has been known for more than a decade that female ESCs present lower DNA methylation levels than male ESCs, it was therefore logical to try to understand if during reprogramming these gender differences were present. Indeed we found that there are sex differences in the remodelling of these methylation marks, with female cells having to undergo more profound loss of DNA methylation in order to forget their differentiated identity. Furthermore, when global DNA demethylation in females is impaired, the cells lose some of their differentiation potential. It will be interesting to investigate this further to see whether the sex specific differences in DNA demethylation seen in our experiments are connected to differences in developmental potential between female and male iPSCs.

iPSCs can be used to study how cells react to new drugs and if these new drugs can be used to treat a specific disease. Moreover, iPSCs technology opens the possibility of obtaining cells made from a patient’s skin to treat their own disease, which would avoid the risk of immune rejection. iPSCs may hold the key to replacing cells and tissues in the future. However, this use of iPSCs is still theoretical and as researchers aim to better understand the reprogramming process it is clear that the gender aspect of this research as to be taken into account and may be important to utilise these cells to their full potential.

*Milagre et al, 2017, Gender Differences in Global but Not Targeted Demethylation in iPSC Reprogramming, Cell Reports, 18:1079-1089

Inês Milagre carried out this work during her time at Wolf Reik’s lab at The Babraham Institute from 2011 to 2016 and is now continuing her work at the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência as a Marie Skłodowska Curie Fellow in the Jansen lab.

Inês Milagre

Laboratory for Epigenetic Mechanisms

Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência